Prime Minister David Lloyd George, in a speech made in Wolverhampton after the Armistice, stated: “What is our task? To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in.” (24 Nov 1918).[1] Following the end First World War, there was a housing crisis. The Housing, Town Planning, etc. (Scotland) Act 1919, one of the Addison Acts, gave local authorities the task of developing new housing and rented accommodation for working people and Government subsidies were made available. The housing estates built became known as ‘Homes fit for Heroes’ and owed much to pre-1914 housing reformers, the Garden City movement and the professionalisation of Town Planning.

Hamilton’s elected representatives were not slow to respond; the Housing Committee agreed on 10 December 1918 to prepare estimates and particulars as ‘housing was urgently required’.

“There was read a letter from the Local Government Board expressing their pleasure that the Council would be prepared to undertake a scheme for 200 to 250 houses… adding that their Architectural Inspector would be prepared to confer and assist the local authority as to lay-out and type of houses.” Hamilton Advertiser, 14 Dec 1918 [2]

It is clear from the December 1918 newspaper report that the Local Government Board for Scotland’s (LGBS) Housing Inspector had visited the burgh and encouraged councillors to proceed on the basis that subsidies would be provided; the legislation was not introduced to the House of Commons until April 1919.

Hamilton’s ‘room and kitchen’ homes

This was not Hamilton’s first foray into providing council homes for working people. Hamilton town councillor Henry Shanks Keith presented a paper by the burgh’s surveyor to the Ballantyne Housing Commission in March 1913; this explained the burgh built dwellings under Part III of the Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890.[3] They had feued an area of ground and built a two-storey tenement to a balcony system design, as recommended by the LGBS, at a cost of £2996. This block consisted of seven single houses and 16 double ones (i.e. either a single apartment 13ft 4ins by 12ft 10ins or a two-apartment ‘room and kitchen’ – 13ft by 9ft 7ins and 16ft 2ins by 12ft; the rooms were all 9ft 6ins high). The houses had shared drying greens and wash houses, plus a coal store and garden plot to each house.

Despite all of these 13 houses being occupied by “a good class of tenants”, there was difficulty in getting an ‘adequate return’ (1906-12).

“…if houses are erected by a municipality, that the community have to face the fact that they are investing at the cost of the rates in the capital necessary to construct the houses and that they cannot, without charging onerous rents, recover capital and interest in the rents.” Henry Shanks Keith, JP ex-Provost and town councillor of Hamilton, 13th March 1913 [4].

Despite its modest nature, the whole of this early scheme was never completed; two-thirds of the land was not occupied by houses as originally intended and became a children’s playground and garden plots. In 1911, 71 per cent of all houses in Hamilton had either one or two rooms; this was typical in Lanarkshire mining districts.[5]

Developing Glenlee

In 1915 the LGBS Architectural Inspector John Wilson told the Ballantyne Housing Commission the Burgh of Hamilton had a ‘far-sighted policy’ of buying land around the burgh, as it became available, out of the common good fund and thus do not need to pay ‘extortionate prices for hospital and other sites’. This meant the town was in a good position to proceed after the war.[6] One such site was Glenlee a triangle of land to the south of High Blantyre Road and north of Udston Road, north-west of the town centre; it had belonged to Glenlee House [NLS one-inch OS map 1895; 25-inch OS map 1897].

Special council meetings were held in March 1919; these were attended by architects from local firm Cullen, Lochhead & Brown – appointed in December 1918 to work with the burgh surveyor on plans and designs.[7] By March 1919 there was a plan to build 236 houses at Glenlee and proposals had been exhibited at the public library. The layout was to be on Garden City lines with about 11 houses to the acre. There was general agreement the ‘one-roomed house’ had had its day.

Deputations heard at the March meetings make it clear there had been detailed examination and discussion locally of the plans. Union representatives were anxious rent levels would be unaffordable; some men wanted fewer but larger rooms; the architects said some rooms would be enlarged. A number of women were heard and their remarks reported:

“Mrs Murdoch speaking on behalf of working-class women, said it had been their desire to live in a cottage type of house, and she was glad to see that type in the plans before them.”

“Mrs Kerr also favoured the cottage scheme, remarking that such a type of house would greatly help a working woman in the management of her household work and the children.”

“Mrs Robertson said they preferred three rooms and a kitchen. …with the bedrooms upstairs.” Hamilton Advertiser, 29 March 1919 [8]

This 29 March 1919 newspaper report also makes reference to the Women’s House-Planning Committee Report from 1918 and the plans from the 1919 architectural competition.[9; 10] This shows these documents reached decision makers and they were using them.

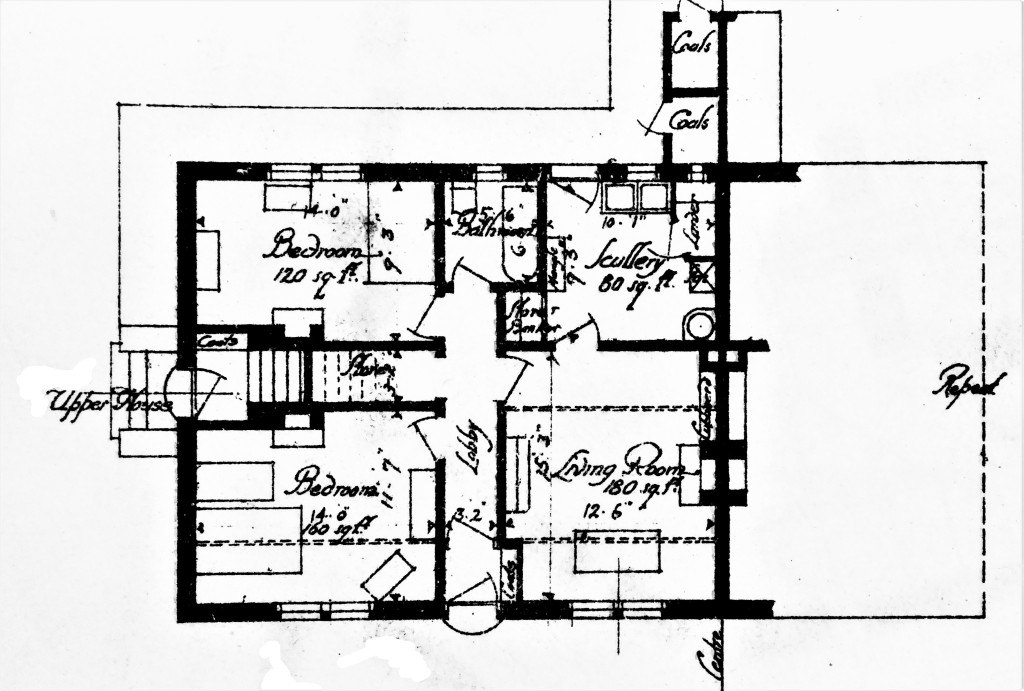

In November 1919 Hamilton town council had two days to decide what mix of housing they wanted to meet the deadline set by the Board of Health (which had taken over from the LGBS).[11] They decided all the houses would have a scullery and a bathroom. The term kitchen is what we would now understand as being the living room. They were kitchens because traditionally the main fire was lit in a kitchen range in the main living room. A two-rooms and kitchen house, thus had two bedrooms and a living room; many of these smallest houses were built as four-in-a-block flatted dwellings.

The houses at Glenlee

The layout of the estate at Glenlee is evident from later Ordnance Survey maps. The houses were mainly semi-detached, four-in-a-block or in short terraces of four, all spaciously laid out with private gardens and pockets of shared open space.

Flatted dwellings, or four-in-a-block, were a compromise between a cottage-style of house and a block of tenement flats, and a popular choice with Scottish councils. John Wilson included drawings of this design in his evidence to the Ballantyne commission, and these were among his designs published circulated to councils.[11]

Hamilton’s architects Cullen, Lochhead & Brown took a second prize for their portfolio in the architectural competition held by the LGBS in association with the Institute of Scottish Architects.[10] The results were issued 22 February 1919 and the plans exhibited in the Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh, from 26 Feb 1919 to 4 March 1919. A selection of published plans were sent to local authorities. These plans give us some idea what Cullen, Lochhead & Brown designs for the Hamilton houses were like inside.

Each four-in-a-block house had its own entrance and private garden. Where there was a town gas supply, gas stoves and water heaters could be located in sculleries. Gas stoves at this time were often rented from the gas corporation.

Designs for larger semi-detached houses, such as those in Russell Street (above), included two reception rooms, labelled living-room and parlour, plus a scullery and bathroom. The parlour could be used as a downstairs bedroom.

The smaller style semi-detached houses in Russell Street (above) appear to have been built to the same design as the four-house terrace round the corner in Udston Road. These houses are likely to have had a large living room, a scullery, a bathroom (perhaps on the ground floor) and two bedrooms upstairs.

The houses on the Glenlee estate provided a complete break with the old room and kitchen houses and helped to set a new standard of accommodation, separating cooking and eating from sleeping along with indoor plumbing and bathrooms. Despite higher than average rents, demand for the new houses was high. Hamilton went on to lay out and build large new housing estates with crescents and avenues transforming the burgh, as can be seen on the O.S. six-inch maps revised in 1938 and published after the end of the 1939-45 World War.[13]

A council home nation

There was a succession of housing Acts in the inter-war period tweaking the level of subsidy and the emphasis on who should be provided for and what should be provided. By 1944 inter-war housing was seen as a good news story and the concept of subsidised council housing was firmly established In Scotland.

“The decision in 1919 that the State should assume some direct measure of financial responsibility for the housing of the working classes resulted in a substantial improvement in the general level of housing conditions, with the result that out of about 1,300,000 houses occupied in Scotland at the present date over one-quarter, or about 350,000, have been provided since the last Great War. Of this number, 247,000 have been built by local authorities with the aid of subsidy under the various Housing Acts.” ‘Planning our New Homes’ (1944) The Scottish Advisory Committee (pp9-10) [14]

Between 1919 and 1941, 70 per cent of new houses in Scotland were built by local councils.[15] By the mid 1970s over half of all homes in Scotland were council owned. This dominance of council house provision in Scotland was not replicated throughout the UK. By contrast, most new houses built in the decades after the end of the First World War in England and Wales were built by the private sector without subsidy.

REFERENCES

- George Campbell Gosling (2013) Lloyd George’s Ministry Men. OER, Learning Technologies Group, University of Oxford. http://ww1centenary.oucs.ox.ac.uk/body-and-mind/lloyd-georges-ministry-men/

- Hamilton Advertiser, 14 December 1918 [BNA].

- Henry Shanks Keith (1913) Evidence given before the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Industrial Population of Scotland (1921) Edinburgh: HMSO. Vol. 1 (pp93-109); Paper by W.H. Purdie Vol. 4 app. (p10). Consulted at the NLS [GRG.6].

- Henry Shanks Keith (1913) Evidence given before the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Industrial Population of Scotland (1921) Edinburgh: HMSO. Vol. 1 (Para. 19, p95). Consulted at the NLS [GRG.6].

- Henry Ballantyne (1917) Report of the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Industrial Population of Scotland, rural and urban. Edinburgh: HMSO. [Cd. 8731] (p137, para.941). Available from: https://archive.org/details/reportofroyalcom00scotrich

- John Wilson (1915) Evidence given before the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Industrial Population of Scotland (1921) Edinburgh: HMSO. Vol. 3, Qu. 44,011 (p2009). Consulted at the NLS [GRG.6].

- Hamilton Advertiser, 22 & 29 March 1919 [BNA].

- Hamilton Advertiser, 29 March 1919, page 3 [BNA].

- Local Government Board for Scotland. Women’s House-Planning Committee Report. (1918). Edinburgh: HMSO [British Library shelfmark Wf1/7931].

- Local Government Board for Scotland (1919) Selected plans and designs of the successful competitors in the Architectural Competition. Local Government Board for Scotland and the Institute of Scottish Architects. London: HMSO.

- Royal Commission on Housing in Scotland (1917) Special report with relative specifications and plans, prepared by Mr John Wilson FRIBA on the design, construction, and materials of various types of small dwelling-houses in Scotland. Edinburgh: HMSO [Cd. 8760] Available from archive.org: https://archive.org/details/specialreportwit00grearich

- Hamilton Advertiser, 22 Nov 1919, page 3 [BNA].

- NLS maps O.S. six-inch revised 1938, published c.1948, Lanarkshire Sheet XVII.NE https://maps.nls.uk/view/75651081 and Sheet XVII.NE https://maps.nls.uk/view/75651081

- The Scottish Advisory Committee (1944) Planning our New Homes. Department of Health for Scotland. Edinburgh: HMSO. [Cmd 6552] Available from archive.org: https://archive.org/details/b32175024

- The Scottish Advisory Committee (1944) Planning our New Homes. Department of Health for Scotland. Edinburgh: HMSO. [Cmd 6552] Available from archive.org: https://archive.org/details/b32175024 (page 11 – Table I).

First published 22 June 2024

Except where otherwise stated, The Past and Other Places by JKW (Kay Williams) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License