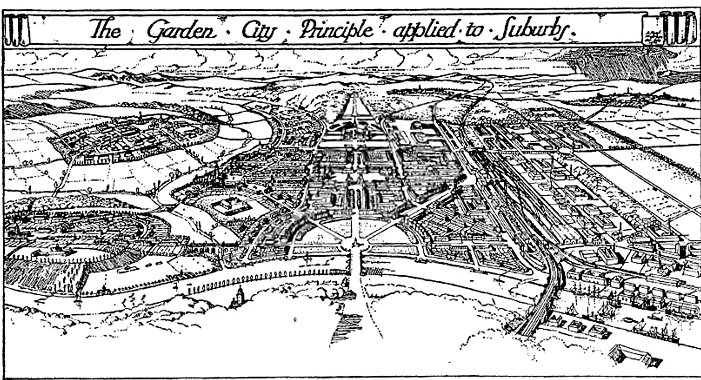

The establishment of a new naval base on the Fife coast of the Firth of Forth at Rosyth, first proposed in 1903, was seen as an opportunity to develop a new civic model settlement combining the best of town and country; an example of Garden City planning.

“Looked at today, the interesting thing is the astonishing range and variety of house types and the evocative sense of the Garden City which they convey.”

Tom Begg (1987) page 47.

![Houses clustered around a village-style green on Backmarch Road in Rosyth. [CC BY-NC-ND]](https://thepastandotherplaces.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/dsc_0016.jpg?w=723)

In 1908 The Scotsman newspaper published a letter from Thomas Adams, of the Garden City Association, arguing the new town at Rosyth should be planned on Garden City principles [15 April 1908]. Adams, originally from Edinburgh, was the first manager of Letchworth Garden City, which put into practice social reformer Ebenezer Howard’s vision set out in his book To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path To Real Reform (1898), later republished as Garden Cities of To-Morrow.

Ambitious plans faded as construction of the naval base was delayed and a proposed tramway between Rosyth and Dunfermline was shelved.

“The local feeling on the subject of co-operation with Government is not particularly warm or confident; and if a model city is to be built, the Admiralty and the Exchequer will have to show much more enterprise and generosity than they have hitherto done to ensure local faith or expectancy with regard to their schemes.”

The Proposed Garden City At Rosyth, The Times, September 4 1908 (p10).

Historian Mark Swenarton, who examined Admiralty papers now held in The National Archives, found that neither the Admiralty nor Dunfermline council wanted to take responsibility for building houses and financial assistance was not initially forthcoming to enable a public utility society to do so [Swenarton (1981) pp 44-47]. By 1914 dock construction was well under way and the Admiralty estimated 3,000 houses were needed. One of the sticking points was that a public utility society would need to raise one-third of the initial capital of the £1 million needed to qualify for state assistance under the 1909 Town Planning Act (equivalent to almost £90 million in 2022).

The delays meant workers were housed in temporary hutted encampments officially known as Rosyth Bungalow Village but nicknamed ‘Tintown’. Tom Begg describes the living conditions as primitive and ‘something of a scandal’ with 26 people to a hut [Begg (1987) pp44-46]. A village hall was officially opened in November 1913; an occasion at which villagers were presented prizes for tidiness [The Scotsman 24 Nov 1913].

Eventually, there was a meeting of minds between the Admiralty, the Local Government Board for Scotland and local politicians; provisions in the 1909 Town Planning Act were ‘adapted to Scottish requirements’ [The Scotsman 6 June 1914]. Dunfermline Town Council approved the Rosyth town planning scheme in July 1915. The Scottish National Housing Company was set up to provide houses for employees at Rosyth naval dockyard; 50,000 £1 shares were taken by the town council with the Public Works Loan Board lending the money at 4 per cent interest over 60 years [The Scotsman 31 July 1915].

Raymond Unwin was appointed expert advisor to the Admiralty in connection with the Rosyth scheme in 1913 and his assistant Alfred Hugh Mottram worked on the layout. Mottram’s plan of the first, second and third phases of the development shows how the streets were laid out in curves around the straight wide arterial routes formed by Queensferry Road, Castlandhill Road and King’s Road. The plan also shows how Mottram saw the town developing to the west. Mottram’s later plan from 1936 shows what was actually built and the inclusion of cultural, shopping and community facilities.

As architect for the Scottish National Housing Company (SNHC), Alfred Mottram designed around 1,500 houses for Rosyth. Other architects and practices included Greig & Fairbairn, James Bow Dunn, Haxton & Walker and James Miller [See: Scottish Architects].

![Four-in-a-block flatted houses in Admiralty Road, Rosyth. [CC BY-NC-ND]](https://thepastandotherplaces.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/dsc_0052.jpg?w=1024)

![Terraced housing in Queensferry Road, Rosyth. [CC BY-NC-ND]](https://thepastandotherplaces.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/dsc_0004.jpg?w=1024)

The housing at Rosyth was mainly in short terraces of four, six or eight houses, with a some taking the four-in-a-block flatted form and some semi-detached houses. The layout followed the new principles of town planning with broken frontage lines giving variety, areas of green space with trees lining the roads and private gardens front and back. The designs for Mottram’s type K houses, dated 1916, state 31 of this type were contracted for.

In Cottage Plans and Common Sense (1902) Unwin’s manifesto for the improved cottage stated cottages should be self-contained, oriented so the sun reaches as many rooms as possible and free of back projections which caused shadows. The living room should be large, bedrooms large enough for healthy living and there should be a separate internal bathroom and WC. These principles were followed by Mottram and the other architects who designed houses for Rosyth.

![A row of terraced houses in Queensferry Road in Rosyth. [CC BY-NC-ND]](https://thepastandotherplaces.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/dsc_0041.jpg?w=723)

The first houses were occupied at Rosyth from 1916 and an official opening was held in May. In his opening speech, Mr JR Findlay, the chairman of the SNHC, commented that 20 years previously tenements would have been built, but ‘a great deal’ had been learned since about providing urban housing and, as most occupants were from south of the Border, they had ideas ‘in advance of our own native population’ and thus the houses were in accordance ‘with English ideas’ [The Scotsman, 26 May 1916]. Perhaps a surprising statement given that John Ritchie Findlay owned The Scotsman newspaper.

In the summer of 1918 the Scottish Women’s House-Planning Committee, appointed by Robert Munro Secretary for Scotland to submit recommendations ‘from the housewife’s standpoint’, visited Rosyth [The Scotsman, 27 June 1918]. Their report, published in October 1918, described 1,600 houses built or being built at Rosyth and in all 17 types of houses with a living room and two or three bedrooms [British Library shelfmark Wf1/7931]. Most had electric light and all of them had gas for cooking. A bathroom, larder, scullery and coal cellar was provided for every house. They did find faults with narrow staircases, sloping bedroom ceilings and bathrooms being too small and opening off sculleries. They requested better washing facilities, storage and access to the back door (for mid terraced houses) – something that was remedied in later designs.

According to both Begg and Rosenburg the houses were not initially popular with the occupants who complained of awkward shaped rooms, draughts, poor rear access and high rents [Begg (1987) pp 48-49; Rosenburg (2016) p149]. Rosenburg, in a chapter that takes an overview of Scottish housing developments during the First World War, comments that Rosyth became the largest of the permanent wartime housing schemes but it was a ‘mixed success’ [Rosenburg (1916) pp 144-149]. Furthermore the SNHC failed to achieve its target maximum dividend of five per cent [Begg 1987 p48].

Today the houses built at Rosyth are quite obviously cared for by their residents and, while some front gardens have been paved to provide off-street parking, many well-tended front gardens are flourishing.

Useful links and sources

A brief introduction to Garden Cities by Historic England: https://heritagecalling.com/2016/02/18/a-brief-introduction-to-garden-cities/

The development of Rosyth is discussed in the following books:

- Mark Swenarton (1981) Homes fit for Heroes: The politics and architecture of early state housing in Britain. London: Heinemann. https://www.worldcat.org/title/7987677

- Tom Begg (1987) 50 Special Years: A study in Scottish Housing. SSHA London: H Melland. https://www.worldcat.org/title/23901309

- Lou Rosenburg (2016) Scotland’s Homes fit for Heroes: Garden City influences on the development of Scottish working class housing 1900 to 1939. Edinburgh: The Word Bank. https://www.worldcat.org/title/957129002

The houses built at Rosyth were an early form of social housing. New legislation in the early twentieth century encouraged town planning and the development of housing schemes.

- The History of Council Housing from the University of the West of England: https://fet.uwe.ac.uk/conweb/house_ages/council_housing/index.htm

- An outline history of social and council house development by Martin Stilwell ; http://www.socialhousinghistory.uk/wp/

- Links to key town planning and council housing legislation are available by theme from the UK Parliament website: https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/overview/

Contemporary newspapers often have accounts of new Garden City developments and post 1919 Act local authority housing (including committee meetings). The amount of coverage and the tone varied according to the editorial policy and political persuasion of the newspaper. Digital newspaper collections are sometimes available via libraries and family history societies either free or for a reduced fee.

- The Scotsman Digital Archive, 1817-1950 (ProQuest Historical Newspapers) and The Times Digital Archive, 1785 – 2014 (Gale Primary Sources), have been accessed via the National Library of Scotland.

- The British Newspaper Archive, by the publishers of Find My Past, gives access to a huge and growing collection. It is worth checking which titles have been digitised and are which years are available (coverage is incomplete): https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/titles

The Internet Archive has scanned copies of some contemporary Garden City movement publications, which can be downloaded in various formats including pdfs.

- Ebenezer Howard (1898) To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. London: Swan Sonnenschein. https://archive.org/details/tomorrowpeaceful00howa

- Ebenezer Howard (1902) Garden Cities of To-Morrow. London: Swan Sonnenschein. https://archive.org/details/gardencitiesofto00howa

- First Garden City Limited (1911) Letchworth Garden City in fifty-five pictures. London: Halton House. https://archive.org/details/cu31924094635368

- Ewart G Culpin (1913) The Garden City Movement Up-to-Date. London: The Garden Cities and Town Planning Association. https://archive.org/details/gardencitymoveme00culpuoft

The Garden City Association is better known to us today as the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA): https://tcpa.org.uk/about/our-history/

Raymond Unwin was a major figure in early town planning and housing design.

- Raymond Unwin (1902) Cottage Plans and Common Sense. Fabian Society Tract 109. London: Fabian Society. https://di.gital.library.lse.ac.uk/collections/fabiansociety/tracts1902-1918

- Raymond Unwin (1909) Town Planning in Practice: An introduction to the art of designing cities and suburbs. London: T. F. Unwin. https://archive.org/details/townplanninginp00unwigoog

- Raymond Unwin (1912) Nothing Gained by Overcrowding!: How the garden city type of development may benefit both owner and occupier. London: P.S. King & Son, for the Garden Cities & Town Planning Association. https://archive.org/details/cu31924014454833

- Willie Miller Urban Design + Planning (WMUD) worked on a masterplan for Gretna in 2007 and have blogged about Raymond Unwin and Gretna, where munitions workers were housed: https://www.williemiller.com/raymond-unwin-and-gretna.htm

Reliable biographies of architects and their practices or firms can be found on the following sites:

- The AHRnet Biographical Dictionary of British and Irish Architects 1800-1950: https://architecture.arthistoryresearch.net/

- The Dictionary of Scottish Architects (DSA) for architects known to have worked in Scotland during the period 1660-1980: http://www.scottisharchitects.org.uk/

The Scottish Women’s House-Planning Committee report, chaired by Helen Kerr, was published by HMSO in Edinburgh in October 1918 and distributed to local authorities and others, but it was not given a Command paper number and is consequently difficult to track down.

- Local Government Board for Scotland. Women’s House-Planning Committee. Report (1918). Edinburgh: HMSO [British Library shelfmark Wf1/7931]

There was a separate Women’s Housing Sub-Committee dealing with England and Wales for the Ministry of Reconstruction, chaired by Lady Gertrude Emmott, which published an interim report in May 1918 and a full report in 1919. These can be obtained via ProQuest UK Parliamentary Papers. Many libraries have a subscription: these have been accessed via the National Library of Scotland.

- Ministry of Reconstruction. Advisory Council. Women’s Housing Sub-Committee. First interim report. (1918) [Cd 9166].

- Ministry of Reconstruction. Advisory Council. Women’s Housing Sub-Committee. Final report. (1919) [Cd 9232].

The photographs of Rosyth are the author’s own and can also be viewed at https://flic.kr/s/aHBqjAbEk2 They are licensed: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 [CC BY-NC-ND].