Dr Elizabeth M McVail was working as an inspector at the Local Government Board for Scotland when she gave evidence before the Ballantyne Royal Commission on Housing on 14 March 1913 [1]. She had visited 36 farms to inspect potato pickers accommodation during the summer of 1910. Dr McVail explained to the commissioners that farmers sold potatoes by auction in lots to different dealers and usually the dealers hired squads of workers. The farmer had to accommodate the squad while the dealer provided other necessities. Most the pickers came from the west of Ireland in June and remained in Scotland for five to six months. They started in the Carrick district, moved on to the rest of Ayrshire and shifted later to Lothians; a few pickers finished up in Perthshire or Angus (Forfarshire) in November.

“These merchants employ squads of workers under the direction of gaffers, who go from farm to farm in different districts to dig the potatoes as they become ready. … each squad consisting as a rule of from 20 to 30 workers.” Minutes of Evidence given before the Ballantyne RC (1921) Vol 1, page 119.

Dr McVail stated that most potato pickers were housed in farm buildings such as lofts, barns, potato houses, byres, loose boxes and other out houses. The potato dealer provided blankets and potatoes to eat, while the farmer provided a place to sleep, straw and coals. The exact nature of the facilities varied widely.

“At some farms improvements had recently been carried out, such as the erection of new sanitary accommodation and of partitions in existing outbuildings for the separation of the sexes. In other cases the farmers were apathetic…” Minutes of Evidence given before the Ballantyne RC (1921) Vol 1, page 119.

Later Dr McVail presented her research in the form of a postgraduate thesis which can still be accessed from the University of Glasgow [2].

Evidence in the 1921 census

The 1921 census was delayed until 19th June, due to industrial unrest, and this means there is a greater chance of finding seasonal workers in temporary accommodation on farms. The census enumerators’ instructions anticipated the need to enumerate people sleeping temporarily in makeshift accommodation or tents [3].

The police were asked to assist as far as possible and enumerators were asked to get in touch with local police officers to secure their cooperation.

“Until the 1930s, early potatoes grown in the Girvan district had a virtual monopoly in the Scottish early potato market.” Holmes (2005) p12.

Farmer John Hannah of Girvan Mains, reporting on Ayrshire to the Board of Agriculture in 1907, had commented that seasonal casual workers used to be got for farm work from towns and villages. These had been replaced by large numbers of Irish labourers, principally girls, who come over in June [4]. Mr Hannah was well known for growing ‘Ayrshire earlies’ and his farm was visited by Americans Grubb and Guildford [5].

In a plate from Grubb and Guildford’s book, you can just make out that the pickers are putting the potatoes in barrels. These valuable Ayrshire early potatoes were transported to Glasgow by train for sale. Although horse-drawn spinners were used to dig out maincrop potatoes for potato pickers, the early crop potatoes were smaller and more easily damaged. In the first quarter of the twentieth century Ayrshire earlies were usually dug using a specialist fork with blunt-ended prongs known as a graip.

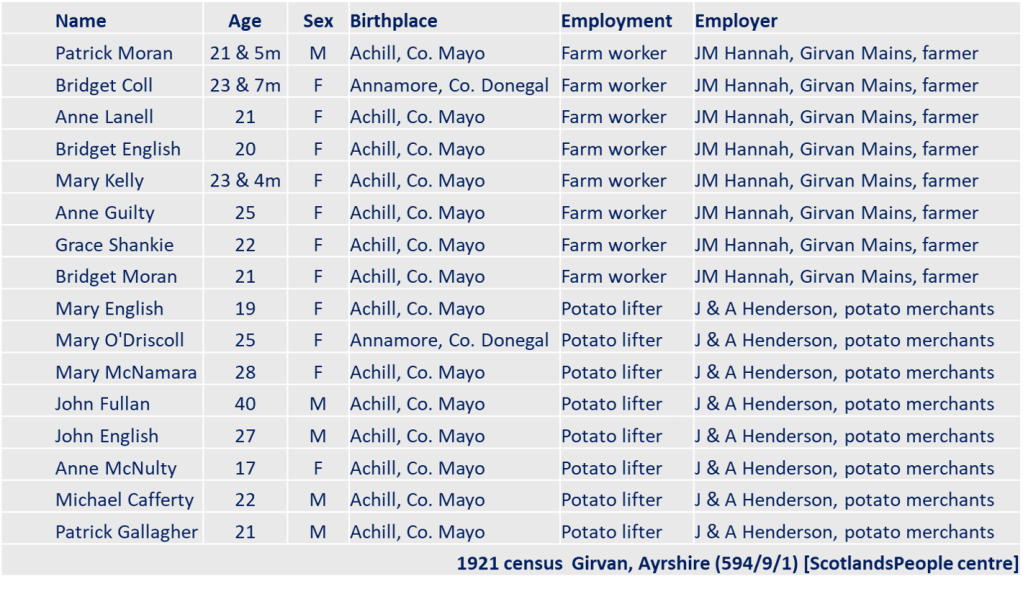

In the 1921 census we find 16 people accommodated in a barn on the farm at Girvan Mains. Half were described as farm workers and employed directly by the farmer John Hannah and the other half as potato lifters employed by potato merchants J & A Henderson [6]. All were single and they ranged in age from 17 to 40, but the majority were in their early twenties. Out of the 16 workers 11 were young women; 14 were born on the island of Achill, the other two on the island of Annamore – both islands are off the west coast of Ireland.

At the same time there were 25 potato lifters housed in barns at Currah farm, Girvan, in 1921 [7]. These two squads were employed by two Forfar merchants G&D Maxwell and James Shields & Co and two-thirds were born in Ireland. A further 40 pickers were housed in the barn at Chapeldonan farm, Girvan [8]. This large group was employed by the Cooperative Wholesale Society, all of them born in County Mayo or County Donegal.

Tragedy and improvement

If accommodating a large number of young people in barns and giving them coal, for cooking and heating, and straw or hay, as part of their bedding, sounds like a recipe for disaster, it was. A fire at Kilnford farm, Dundonald, Ayrshire in September 1924 suffocated nine workers employed by the Cooperative Wholesale Society [9].

The Scottish Board of Health issued model byelaws intended to improve conditions, which local authorities could adopt, but the process was slow and not particularly effective; legislative efforts were still being made to improve standards in the mid-1960s [10].

Who was Dr McVail?

According to the medical register for 1913, Elizabeth McVail graduated from the University of Glasgow in 1906 as a Bachelor of Medicine (MB) and Bachelor of Surgery (ChB). She registered as a medical practitioner on July 24 1906 and received a diploma in public health from the University of Cambridge in 1908 [11]. In 1913 her address was given as Hatfield Drive, Kelvinside, Glasgow.

Women struggled to qualify as doctors. The Universities (Scotland) Act 1889 was a gamechanger as it allowed women to be admitted with the same status as men. The number of women qualifying rose from four in 1881 to 60 in 1901 [12]. It was 1894 before the first women, Marion Gilchrist and Alice Louise Cumming, qualified in medicine at a Scottish university. They studied at Queen Margaret College, University of Glasgow, where women were taught medicine separately from men from 1883 [13].

“Female students and doctors found it easier to gain access to hospitals with women or children’s diseases. In 1890, Glasgow Sick Children’s Hospital admitted female students and by 1892 had twelve QMC students and two male students working in its wards.” A Significant Medical History, University of Glasgow School of Medicine, Dentistry and Nursing.

A news report on the health of schoolchildren, notes that Dr Elizabeth McVail was the inspector for the Sowerby Bridge district in 1909 (Calderdale in West Yorkshire) [14]. She had been appointed the previous year [15]. The Children Act 1908 had made the medical inspection of school children compulsory.

In 1910, Elizabeth McVail became ‘lady inspector to the Board’ in Edinburgh [16]. Giving her evidence to the Ballantyne commission was one of the final things she did at the Local Government Board for Scotland as in 1913 Dr McVail was appointed as a medical assistant in London County Council’s public health department (at £400 a year); it was noted that lady doctors ‘must resign if they marry’ [17; 18]. In becoming a public health specialist, Dr McVail followed in family footsteps.

Elizabeth Maud McVail was born in Kilmarnock, Ayrshire, on 17th September 1881 to John Christie McVail, a medical practitioner, and his wife Jessie Shoolbred (m.s. Rowat) [19]. In the 1891 census the family were living at 1 Caledon Street in Govan/Partick, in a house with six rooms with windows, part of an upmarket sandstone tenement block [20]. The whole family were born in Kilmarnock. Father John (41) was a medical officer, Jessie was 39 and they had four children: John (12), Elizabeth (9), James (6) and Jessie (1). Mother Jessie’s brother John Rowat (28) was a registered general practitioner. General domestic servant Janet Gibb (32) completed the household.

The medical register for 1913, shows Elizabeth’s father Dr John C McVail, who graduated from St Andrews University in 1873 and 1875, received qualifications in public health from the University of Glasgow and the University of Cambridge in 1885. Elizabeth McVail’s older brother John B McVail had registered as a medical doctor in 1904 and was licensed by the Royal colleges of surgery and physicians in England [11]. The younger John seems to have practised mainly overseas in India and Chile [20; 21].

John C McVail and his brother David C McVail, the sons of a Kilmarnock master tailor, were both unusually distinguished medical men. According to Who Was Who John Christie McVail (1849-1926) became president of the Society of Medical Officers of Health and president of the Glasgow branch of the British Medical Association. He was a member of the Scottish Board of Health, served on the National Health Insurance Commission and was the Crown Member for Scotland of the General Medical Council, 1912–22 [22]. Dr John C McVail was also an expert on vaccination and was awarded the Jenner Medal in 1922 [23].

Elizabeth’s uncle David Caldwell McVail (1846-1917) taught physiology at Anderson’s College and was Professor of Clinical Medicine at St Mungo’s College, the University of Glasgow’s male medical institution (1889-1906). He also served on Glasgow University’s court, was associated with university reform and knighted in 1910 [24].

The London County Council record of war service 1914-18 lists Hon. Major Elizabeth Maud McVail, Royal Air Force, as undertaking medical service 1918-19 [25]. In the 1921 census Elizabeth McVail (39) was single and employed by London County Council in ‘no fixed place’ as an assistant medical officer. Her address was given as 211 Adelaide Road in Hampstead [26].

An electoral roll for 1924 shows Elizabeth Maud McVail living at 44 Rotherwick Road, Hendon, near Golders Green tube station, and that her parents had joined her [27]. She would have been 43. Rotherwick Road is part of the Hampstead Garden Suburb; the majority of the houses were designed in groups by architects Parker and Unwin (1909-12) and are Grade II listed [28].

In 1960 solicitors Wilkinson, Howlett & Moorhouse invited claims against the estate of retired medical practitioner Elizabeth Maud McVail of 307 Elm Tree Road Mansions, St John’s Wood, London [29]. Dr Elizabeth McVail (78) died, away from home, on 3 April 1960 at Worthing in Sussex [30]. It was a long way from Kilmarnock.

There’s no doubt Dr Elizabeth McVail’s life was notable and that she would have come up against resistance in choosing to study medicine and in building a career in public health. Like many women who chose a profession, pursing it meant foregoing marriage and having a family.

Professor Suzannah Lipscomb has posed the question “How can we recover the lost lives of women?” [31]. She argues the lives of those who women who appear fleetingly are as meaningful as those who left behind a wealth of documentation. We know archivists have been selective about what has been kept. Historians select further from that. We might not be able to fully recover women’s lives from what is available to us now, but we do need to seek out and tell the stories of lost women when we come across them.

References

- Minutes of Evidence given before the Ballantyne RC (1921) Vol 1, pages 114-124.

- McVail, E.M. (1915) An Enquiry into the Housing of Seasonal Workers in Scotland. MD thesis, University of Glasgow. [Download from: https://theses.gla.ac.uk/80979/]

- Census of Scotland 1921 (1921) Instructions to Registrars and Enumerators. Edinburgh: HMSO. [NRS GR06/478/1] https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/census-enumeration-book-1921.pdf

- ‘Workers on the Land: Temporary and migratory labour its effect on agricultural population’ The Scotsman, Edinburgh, 8 Feb 1907, page 10 [via ProQuest].

- Grubb & Guildford (1912) The Potato.

- 1921 census Girvan, Ayrshire (594/9/1, p2) [ScotlandsPeople centre].

- 1921 census Girvan, Ayrshire (594/9/1, p5) [ScotlandsPeople centre].

- 1921 census Girvan, Ayrshire (594/9/1, pp17-18) [ScotlandsPeople centre].

- Holmes (2005) Tattie Howkers: Irish potato workers in Ayrshire. Ayr: AANHS, Ayrshire monographs (31), pp 87-88.

- Holmes (2005) pp 89-98.

- The Medical Register for 1913, p1043 [via FMP].

- David Hamilton (2003) The Healers: A History of Medicine in Scotland. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Mercat Press, p212.

- University of Glasgow, A Significant Medical History: 19th Century, School of Medicine, Dentistry and Nursing, accessed at: https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/medicine/mus/ourfacilities/history/19thcentury/

- Todmorden & District News, Friday 10 September 1909, page 6 [via BNA].

- Halifax Evening Courier, Monday 21 September 1908, page 2; Wharfedale & Airedale Observer, Friday 25 September 1908, page 6 [via BNA].

- Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, Friday 13 May 1910, page 6 [via BNA].

- The Times, May 31 1913 [The Times Digital Archive, via NLS].

- Woolwich Gazette, Tuesday 11 March 1913, page 6 [via BNA].

- Statutory registers Births, Kilmarnock, Ayrshire, 1881 (597/ 710) [via ScotlandsPeople].

- Members list, Calendar of The Royal College of Surgeons in England, 1920, p218 [via FMP].

- Death notice of Anne McDonald McVail, The Times, 6 Feb. 1907, p1 [The Times Digital Archive, via NLS].

- McVail, John Christie (2007) Who Was Who, published online 1 December 2007 https://www.ukwhoswho.com/ [via NLS].

- Royal Society Of Medicine, The Times, 7 July 1922, p5. [The Times Digital Archive, via NLS].

- Sir David C McVail, The Times, 6 Nov 1917, p 9. [The Times Digital Archive, via NLS].

- London County Council Record of War Service 1914-18, p35 [via FMP].

- 1921 census, England & Wales, Hampstead, London, Middlesex (RG15 8/1/25) [transcript via FMP].

- Parliamentary Constituency of Middlesex, Hendon Division, Electoral Registers 1910-32, The British Library (SPR.Mic.P.336/BL.H.40) [via FMP].

- Rotherwick Road, Hampstead Way, Area 5 Character Appraisal (2010), Barnet London Borough & Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, p12 [Download from https://www.barnet.gov.uk/planning-and-building-control/conservation-and-heritage/conservation-areas/hampstead-garden-suburb] .

- The London Gazette (42008), 15 April 1960, page 2770 [downloaded from https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/42008/page/2770].

- England & Wales deaths, Worthing, (Sussex vol 5H, p613, Qu 2, 1960) [via FMP].

- Lipscomb, Suzannah (2021) ‘How can we recover the lost lives of women’, pp178-196 in Carr, H. and Lipscomb, S. (eds.), What is History, Now?: How the past and present speak to each other. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Key sources

Henry Ballantyne (1917) Report of the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Industrial population of Scotland, rural and urban. Edinburgh: HMSO. [Cd8731] Available from archive.org: https://archive.org/details/reportofroyalcom00scotrich

Evidence given before the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Industrial Population of Scotland (1921) Edinburgh: HMSO. Consulted at the NLS [GRG.6]. https://search.nls.uk/permalink/f/sbbkgr/44NLS_ALMA21438320070004341

Grubb, Eugene H, and Guildford, WS. (1912) The Potato: A compilation of information from every available source. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co. Farm Library series. [Downloaded from: https://archive.org/details/potatocompilatio00grub/page/n525/mode/2up]

Holmes, Heather. (2000) ‘As Good as a Holiday’: Potato harvesting in the Lothians 1870 to the present. East Linton: Tuckwell. https://www.worldcat.org/title/42405633

Holmes, Heather. (2005) Tattie Howkers: Irish potato workers in Ayrshire. Ayr: Ayrshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, Ayrshire monographs (31). [Download from: https://aanhs.org/of-further-interest/ or directly as a pdf https://aanhsorg.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/tattiehowkers.pdf]

McVail, Elizabeth Maud (1915) An Enquiry into the Housing of Seasonal Workers in Scotland. MD thesis, University of Glasgow. [Download from: https://theses.gla.ac.uk/80979/]

Last updated 24 November 2023

Except where otherwise stated, The Past and Other Places by JKW (Kay Williams) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License